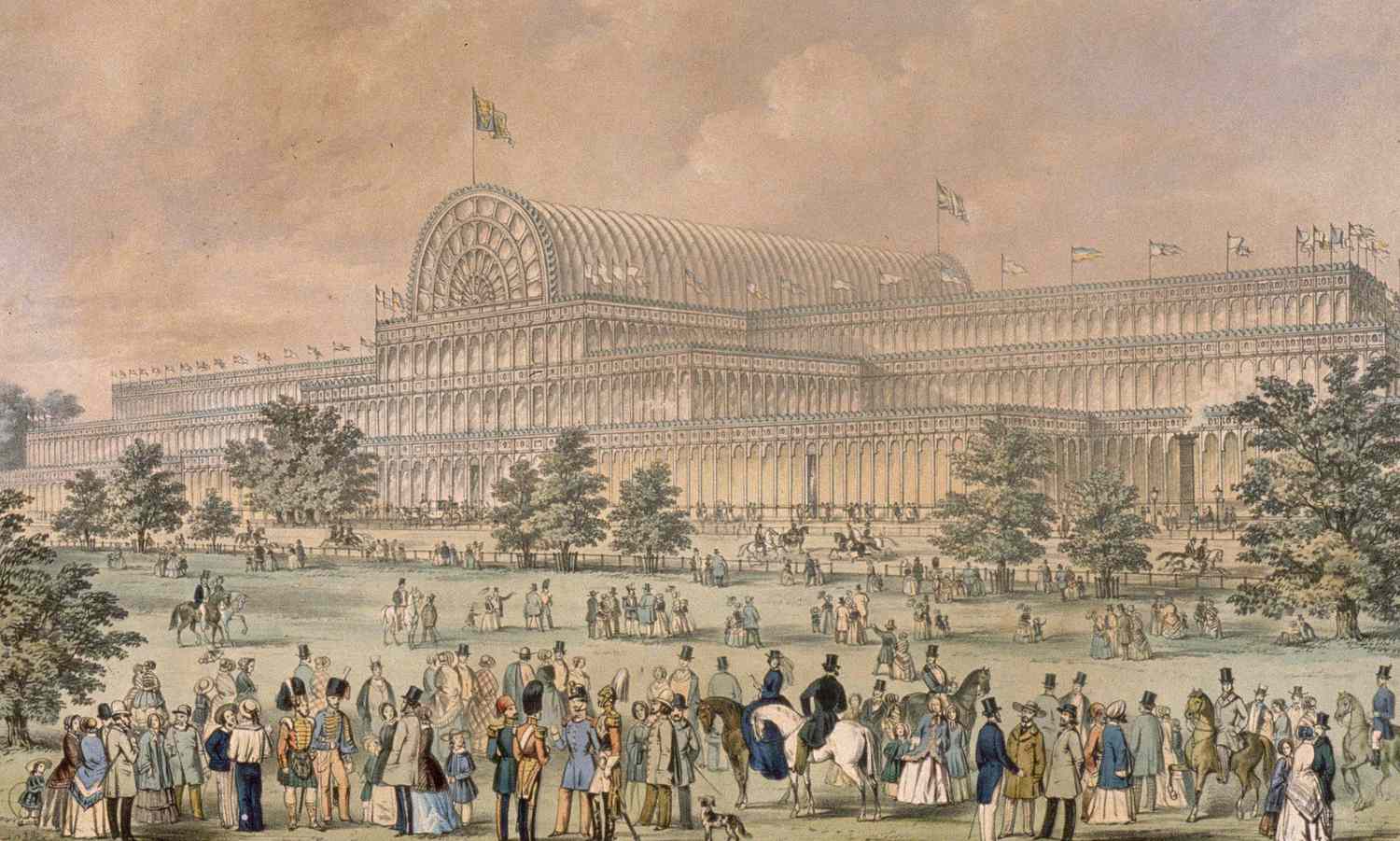

In 1851, London’s Hyde Park transformed into a marvel of human achievement as the Great Exhibition opened its crystal-paned doors to the world. This groundbreaking event marked history as the first-ever World’s Fair, drawing six million visitors over five months to witness technological and cultural innovations from across the globe.

The Great Exhibition revolutionized international trade, cultural exchange, and industrial progress by creating a template for future World’s Fairs and establishing London as a center of global commerce in the Victorian era. The magnificent Crystal Palace, designed by Joseph Paxton, housed 14,000 exhibitors from 40 nations displaying their finest industrial and artistic achievements.

The exhibition’s profits funded the creation of major London museums, including the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Science Museum, cementing its educational legacy. These institutions continue to inspire innovation and learning, serving as lasting monuments to the Great Exhibition’s vision of progress and international cooperation.

Origins and Development of The Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition marked a pivotal moment in Victorian Britain’s industrial and cultural advancement, conceived as a showcase of technological innovation and international trade in 1851.

Role of Prince Albert and Henry Cole

Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband, spearheaded the Exhibition’s creation alongside Henry Cole, a civil servant and inventor. The pair first discussed the idea during the Royal Society of Arts meetings in 1847.

Albert led the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851, establishing the event’s framework and scope. His vision centered on displaying Britain’s industrial might while fostering international cooperation.

Henry Cole managed the practical aspects of organization. He traveled extensively across Europe to promote participation and secured commitments from multiple nations.

Construction of The Crystal Palace

Joseph Paxton designed the revolutionary Crystal Palace in 1850, creating the plans in just nine days. The structure featured unprecedented use of prefabricated glass and cast iron.

The building stretched 1,851 feet long and 408 feet wide, covering 19 acres in Hyde Park. Workers assembled 294,000 panes of glass using Paxton’s innovative ridge-and-furrow roof system.

Construction took just five months, employing 2,000 workers to complete the project. The building’s modular design allowed for rapid assembly and future relocation.

The Crystal Palace’s innovative use of glass created a bright, open space that could house thousands of exhibits while protecting them from Britain’s weather.

Scope and Contents of the Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of 1851 showcased over 100,000 objects across multiple categories, from industrial machinery to fine arts, spread throughout the Crystal Palace’s 990,000 square feet of exhibition space.

Exhibits and Innovations

The exhibition featured groundbreaking technological innovations, including the world’s first public toilets and Colt’s revolving pistols. Industrial machinery occupied the western half of the Crystal Palace, displaying steam engines, printing presses, and textile equipment.

The British display included the Koh-i-Noor diamond, hydraulic presses, and sophisticated agricultural tools. Scientific instruments and manufacturing processes demonstrated Britain’s industrial might.

Notable exhibits included Stevenson’s locomotive “The Iron Duke,” McCormick’s mechanical reaper, and early versions of calculating machines. The Scientific American publication praised the daguerreotype photography equipment and precision instruments on display.

International Participation

Thirty-four nations and colonies contributed exhibits to the Great Exhibition. France sent luxury goods, fine silks, and porcelain, while Prussia displayed steel products from the Krupp works.

The United States showcased agricultural machinery and Samuel Colt’s firearms. Austria exhibited glassware and furniture, with Russia displaying malachite doors and precious minerals.

Indian textiles and Chinese porcelain represented Asian craftsmanship. Colonial exhibits from Canada and Australia featured natural resources and raw materials.

Each country maintained dedicated spaces within the Crystal Palace, creating distinct national sections that highlighted their industrial and artistic achievements.

Cultural and Social Context

The Great Exhibition reflected and shaped Victorian society through its display of industrial progress and cultural values. The event marked a pivotal moment in British social history, drawing visitors from diverse backgrounds and challenging existing class boundaries.

Victorian Era Perspectives

The Exhibition embodied core Victorian ideals of progress, innovation, and moral improvement. Prince Albert and the organizers designed the event to promote education and refined taste among the working classes.

The strict moral code of Victorian society influenced the Exhibition’s organization. Alcohol sales were prohibited, and religious observances were respected through Sunday closures.

Social reformers viewed the Exhibition as a chance to elevate public conduct and knowledge. The event promoted the Victorian belief that exposure to art, science, and industry could improve character.

Public Reception and Attendance

Over 6 million people visited the Exhibition during its five-month run, with attendance peaking at 109,915 visitors in a single day. Workers and middle-class families made up a significant portion of attendees.

Special railway excursions and reduced ticket prices on specific days made the Exhibition accessible to working-class visitors from across Britain.

The mixing of social classes at the Exhibition created unprecedented interactions between different segments of society. Queen Victoria herself made frequent visits, often alongside common citizens.

Visitors generally behaved with remarkable decorum, contradicting predictions of chaos and disorder. This good conduct helped challenge negative stereotypes about working-class behavior.

Economic and Industrial Impact

The Great Exhibition revolutionized global commerce and manufacturing through unprecedented international cooperation and technological exchange. The event generated £186,000 in profits, equivalent to millions in today’s money.

Advancements in Industry

The Crystal Palace showcased 100,000 exhibits featuring the latest industrial innovations. Steam engines, mechanical looms, and new manufacturing processes demonstrated Britain’s industrial might while inspiring technological advancement across Europe.

Foreign visitors studied British manufacturing methods and brought new techniques back to their home countries. This knowledge transfer accelerated industrial development in France, Germany, and the United States.

The exhibition’s success spurred investment in new factories and industrial research. British manufacturers adopted innovative production methods seen at the fair, leading to increased efficiency and output.

Global Trade Implications

International trade expanded significantly following the Exhibition. New commercial relationships formed between exhibiting nations, with Britain’s exports rising 25% in the subsequent five years.

Trade barriers lowered as countries recognized mutual economic benefits. The standardization of industrial processes and measurements gained momentum after manufacturers saw the advantages at the Exhibition.

Raw material suppliers from colonial territories found new markets for their goods. Cotton, wool, and metal ore producers expanded operations to meet growing industrial demand.

The Exhibition established London as a global financial and commercial hub. Banks and trading houses expanded their international operations to facilitate increasing cross-border commerce.

Influence on Future World’s Fairs

The Great Exhibition of 1851 created a blueprint for international expositions that shaped the format and scale of world’s fairs for generations to come. Its innovations in exhibition design, international participation, and cultural exchange established enduring principles that continue to guide modern global exhibitions.

Establishing a Tradition

The success of the Great Exhibition sparked a wave of similar events across major cities. Paris hosted its first international exposition in 1855, directly inspired by London’s model. The Vienna World’s Fair of 1873 adopted Crystal Palace’s revolutionary architectural approach.

These early fairs replicated key elements from 1851, including the classification system for exhibits and the emphasis on industrial innovation. The practice of national pavilions emerged as countries sought to showcase their cultural achievements.

International cooperation became a cornerstone of world’s fairs, with organizing committees following London’s example of inviting global participation. The tradition of awarding medals and certificates to outstanding exhibits continued.

Legacy and World’s Fair Evolution

Modern world’s fairs maintain many principles established in 1851, while adapting to contemporary needs. The focus shifted from purely industrial achievements to include cultural exchange and global solutions.

The Bureau International des Expositions, established in 1928, now regulates world’s fairs using guidelines that trace back to the Great Exhibition’s organizational structure. Major expositions like Expo 2020 Dubai still feature national pavilions and technological showcases.

The educational mission remains central, though the emphasis has evolved from Victorian ideals of progress to sustainable development and international cooperation. Exhibition spaces continue to showcase architectural innovation, following Crystal Palace’s example.

Architectural Significance

The Crystal Palace revolutionized architectural design through its innovative use of prefabricated iron and glass construction, establishing new standards for large-scale public buildings.

Innovations in Design and Materials

Joseph Paxton’s groundbreaking design utilized 294,000 panes of glass and 4,500 tons of iron to create the world’s largest glass structure of its time. The building’s modular construction system allowed for rapid assembly in just nine months.

The structure’s innovative ridge-and-furrow roof design prevented direct sunlight from overheating the interior while creating optimal growing conditions for the exotic plants displayed inside.

The building’s unprecedented scale – 1,851 feet long and 128 feet high – was achieved through standardized components and cast iron framework, setting new possibilities for industrial architecture.

The Fate of The Crystal Palace

After the exhibition, workers dismantled and reconstructed the Crystal Palace at Sydenham Hill in South London in 1854, expanding it to an even larger size.

The relocated structure served as a popular cultural center, hosting concerts, exhibitions, and educational events for 82 years.

On November 30, 1936, fire destroyed the Crystal Palace despite efforts of 89 fire engines and over 400 firefighters. Today, only the building’s stone terraces and sculptured sphinxes remain in Crystal Palace Park.

Lasting Cultural and Educational Contributions

The Great Exhibition of 1851 created an enduring legacy through its support of museums, educational institutions, and cultural initiatives that continue to shape society today.

Museums and Institutes

The Victoria and Albert Museum, established with profits from the Great Exhibition, stands as a testament to Victorian innovation and design excellence. The museum houses many original exhibits from 1851, including intricate metalwork and decorative arts.

The Science Museum and Natural History Museum also trace their origins to the Exhibition’s success. These institutions emerged from the initial collection of scientific instruments and specimens displayed at Hyde Park.

The Royal College of Art, founded in 1837, received significant funding from Exhibition proceeds to expand its educational programs. This investment helped establish Britain’s first formal design education system.

Continued Relevance and Learnings

The Exhibition’s model of international cooperation through cultural exchange influenced modern world’s fairs and expos. Its emphasis on combining art, science, and industry remains evident in contemporary museum curation practices.

The Crystal Palace’s innovative design inspired modern architectural techniques, particularly in the use of prefabricated parts and glass construction methods.

Exhibition principles of public education through interactive displays revolutionized museum practices. This approach transformed museums from elite collections into accessible educational spaces for all social classes.

Many modern science and technology festivals follow the Exhibition’s format of combining public entertainment with educational content.

Victoria and Albert Museum (n.d.) – The Legacy of the Great Exhibition: How It Shaped Museums and Design Education Link

Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 (n.d.) – The History and Impact of the Great Exhibition Link

British Library (n.d.) – The Great Exhibition: A Window into Victorian Britain Link

Science Museum (n.d.) – The Crystal Palace: A Marvel of Victorian Engineering Link

The Royal Parks (n.d.) – Hyde Park and The Great Exhibition of 1851 Link

Historic England (n.d.) – The Rise and Fall of the Crystal Palace Link

BBC History (n.d.) – The Great Exhibition of 1851: The Victorian World’s Fair Link